One night back in 1998, I was reading News of the Weird and one of its stories struck a chord with me. It was about a Minnesota law student whose hobby was requesting copies of the FBI files of celebrities. I can’t remember the student’s name now but it was distinctive enough for me to recognize it the next day when I saw it in my work email inbox. In the email, he introduced himself, explained his hobby and suggested that since the FBI was getting rid of a lot of its old files, I should do a Freedom of Information Act request for their file on Louis Brandeis. (Side note: it turns out the student was a fan of News of the Weird and was delighted to hear that he had been mentioned in it.) So, I filled out the form and then after a few weeks forgot all about it. So, it was a pleasant surprise a year and a half later when I received in the mail a thick envelope from the FBI.

The file ended up being both more, and less, interesting than I expected. Mostly less. It was interesting to see what the FBI decided to keep. But most of what I got was so commonplace that I cannot understand their rationale for keeping it. I assume some of it was donated/mailed to them but some of it had to have been gathered by the agents themselves. A couple items probably had some research value (although I doubt the veracity of them) but of it seems to have little or no value at all. Regardless, here is a list of everything I received, so everyone else can make up their own minds about it.

The first item is a copy of the July 1944 newsletter Money. Money was a publication devoted to … well, I guess, just criticism of the American finance system. And what was Brandeis’ connection to this publication? They used his quote “We must break the money trust or the money trust will break us” on their masthead. That’s it. He is not mentioned in any of the articles and there is no indication that he was ever aware of the newsletter.

Then, there are copies of two book reviews from the New York Times Book Review: on for Felix Frankfurter’s Mr. Justice Brandeis and another for Alpheus Mason’s Brandeis: Lawyer and Judge in the Modern State. There is also a clipping from the October 17, 1934, Muncie Evening Press about Brandeis’ supposed influence on FDR’s New Deal.

There is a page of four short clippings from unidentified and undated from newspapers. One clipping is about Brandeis donating money to the Jewish Labor Federation of Palestine. Another is an announcement of how well a cheap edition of Other People’s Money is selling, while another clipping is about how someone had called for Brandeis to be drafted to rehabilitate America’s financial system. The most intriguing clipping has the headline “Daughter of Justice Brandeis is member of Radical Union.” The radical union? The American Civil Liberties Union. Unfortunately, the photocopying of the article is so bad, most of it is illegible.

There is a page titled “Information taken from ‘Commonwealth College Fortnightly’ Official Organ of Commonwealth College,” which lists contributions made to the college by Brandeis and his wife. Commonwealth College was a Mena, Arkansas school that had been founded by Socialists to train people in socio-economic reform. The school’s radical agenda made it a frequent target of conservatives.

There is a page titled “From Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly Issue of Feb. 8, 1912 Page 144″ which is a retyped excerpt of an article that casts Brandeis in a negative light over his involvement with the United Shoe Machinery Company.

There is a 2 page anti-communistic, and anti-Semitic, pamphlet from 1935 called Justice Brandeis Unfit? Brandeis, and other prominent American Jews such as Benjamin Cardozo, Felix Frankfurter and Albert Einstein are accused of being communist agents.

There is an ad for Other People’s Money with a written note listing the names of Brandeis’ daughters.

There is a typed copy of a letter the FBI received that claimed that Wilson appointed Brandeis to the Supreme Court as a reward for talking a Mrs. (Mary) Peck into not releasing a series of love letters that were supposedly written by Wilson. This letter is accompanied by a letter by J. Edgar Hoover thanking the writer for the letter. (The sender’s named is obscured so that it is impossible to see what it is.)

There is a copy of a column titled “Other People’s Lives” that was written by “the Squire of Krum(?) Elbow” that is from some untitled and undated publication. This anti-Semitic column not only reiterates the Mary Peck charges but also blames Brandeis for America’s entry into World War I and the Communist Revolution in Russia.

There is a copy of a 1954 Westbrook Pegler column titled “We Were Not Told What Brandeis Taught Truman.” Pegler describes a mysterious meeting that took place between Brandeis and Truman and repeats a claim that Brandeis had desired to “wreak havoc” in the United States.

The last item in the folder is probably my favorite. It is a 1941 report by Special Agent J. F. Elich. But it is impossible to tell what the report is about since it is so heavily redacted.

About all I can ascertain from it is that Brandeis did not know the person the agent was inquiring about and that an intermediary (presumably Alice Brandeis) had to act as a go between because she said that “Brandeis did not ever speak over the telephone.”

Filed under: brandeis | Leave a Comment

On November 1, 1912, Brandeis delivered a speech to the Economic Club in New York City about the danger of trusts. An excerpt of the speech was later published in his book The Curse of Bigness under the title “The Regulation of Competition Against the Regulation of Monopoly.” (The entire speech was reprinted in the third volume of the Year Book of the Economic Club of New York, which can be found on Google Books.)

Ninety years later, on July 24, 2023, Federal Trade Commission Chair, and neo-Brandeisian, Lina Khan gave a speech of her own to the Economic Club that harkened back to Brandeis’ speech and looked forward to the future.

In his speech, Brandeis expounded on the ills inflicted upon society by trusts and monopolies, and claimed that the only way to remedy these abuses was to regulate competition in order to prevent trusts from forming in the first place — a philosophy that led to the formation of the Federal Trade Commission.

In her speech, Khan relates how the formation of the Commission led to unparalleled prosperity in America and how America’s abandonment of the policy of regulating competition and its embrace of free markets has erased all those gains. She gives example after example of how corporate concentration has negatively impacted modern life: from skyrocketing health care and pharmaceutical prices, to supply chain disruptions, to widespread economic disparity.

She then talks of how President Biden has signed an executive order to make the regulation of competition a cornerstone of American economic policy, and how the FTC, under her leadership, is working to enact that policy. She describes various of the FTC’s activities, including blocking dangerous mergers, advocating for the elimination of non-compete clauses in employment contracts, investigating outrageous drug prices, and other initiatives.

Overall, her speech is an excellent reminder on the continued relevance of Brandeis’ economic philosophy. You can read her speech on the FTC’s site.

Filed under: brandeis | 1 Comment

Somebody should write a book about the friendship between two of the giants of the Progressive era: Louis D. Brandeis and Robert M. La Follette. As congressman, governor and senator of Wisconsin, La Follette pursued many of the aims of the Progressive movement: tax reform, opposition to railroad and other trusts, direct election of senators, limited hours for workmen and the abolition of child labor. With such views, it was inevitable that Brandeis and La Follette would meet and work together, but they also ended up forming a close bond.

After their first meeting in D.C. in 1910, both Brandeis and his wife Alice became frequent visitors to the La Follette household, and Brandeis would dine at their home whenever he was in town. In 1911, La Follette entered the running to become the Republican presidential nominee. Brandeis supported his friend and did a considerable amount of campaigning for him. But it was all for naught. Rumors of a mental breakdown and the lack of support from the Republican party doomed the campaign. In the end, La Follette only won two states: his home state of Wisconsin and North Dakota. After the primaries, Brandeis transferred his allegiance to the Democratic Party candidate, Woodrow Wilson. Wilson, of course, ended up nominating Brandeis to the Supreme Court, and La Follette was instrumental in getting Brandeis enough Republican votes in the Senate to pass the nomination.

Brandeis’ campaigning for La Follette took place mostly behind the scenes: exhorting people to work for La Follette and writing press statements. I have found one such statement in the collection of Brandeis papers here at the University of Louisville. At the top of the three page document is a note that states (in part) that it was not to be released “unless La Follette carries the Wisconsin primaries.” Since La Follette did just that, I assume that it was published somewhere — presumably in a Wisconsin newspaper. While it is not the most revelatory piece of writing, it does give a good idea of the Progressive philosophy of the early 20th century, and since it has not been reprinted since its original publication (if there was one), I have decided to reproduce it here:

NOT TO BE RELEASED UNTIL APRIL 3, nor UNLESS LA FOLLETTE CARRIES THE WISCONSIN PRIMARIES.

Interview at Washington.

The vote of Wisconsin at yesterday’s presidential primaries is no idle compliment to a favorite son. It expresses the deliberate conviction of the citizens of a great Commonwealth that Robert M. La Follette is by character, ability and experience, the man best fitted to deal, as President, with the grave and fundamental problems before the American people. That judgment is of significance, because it was rendered in a state where La Follette has been known in public life for thirty years and has been tried in every high office within the gift of the people; because it was rendered by his fellow citizens who long and obstinately combatted his principles and policies but finally became convinced of their wisdom and justice, and joining with him have made their state the leader of Progressive thought in America.

No man in public life today expresses the ideals of American Democracy so fully as does La Follette in his thought, his acts, his living. No man in public life today has done so much toward the attainment of those ideals. He is far-seeing, of deep convictions and indomitable will; straightforward, able, hard-working, persistent and courageous. His character is simple. He is patient, save only of wrongs done the people. He has often been called a demagogue, but it is mainly by those who could not conceive of his passionate love for the people, and of his faith in them. He is often said to be too radical; but it is mainly by those who are unable to realize that “nought is abiding save only change”. He used to be charged with insincerity, but even his bitterest opponents have abandoned that charge in the light of recent events.

The greatest problem now before the American people is the demand for social justice and industrial democracy. Our working men enjoy political liberty but, in the main, are subject to industrial despotism and social injustice which, under the Trusts, [have] become particularly oppressive. A large part of our working people are working and living under conditions inconsistent with American standards and ideals, and indeed with humanity itself. The condition of a large body of the Steel workers toiling twelve hours a day, seven days in a week at less than a living wage — while the Steel Trust exacted from the consumer in ten years more than $650,000,000 in excess of a liberal return on the capital originally invested — is one of the results of this industrial absolutism. It is obvious that present conditions cannot continue. Either our people will lose their political independence, or they will acquire industrial independence. We cannot exist half free and half slave.

The problem is how to remove these flagrant abuses of our industrial system; how to secure industrial liberty while preserving what is good in our institutions — the energy, enterprise and persistence characteristic of Americans.

For the solution of that great problem, the American people need a leader with courage, ability, constructive power and vision; and perhaps above all, that deep and passionate sympathy with the common people which made Lincoln the greatest of all Americans.

La Follette possesses these qualities. He sees clearly and feels deeply the disasters which must attend a continuance of industrial absolutism. He appreciates fully the needs of business, but also that the biggest of all business is that of the United States, which is pledged to secure life, liberty and the opportunity to pursue happiness to its 90,000,000 stockholders.

La Follette will have due solicitude for the needs of business, but he will never forget that business was made for man and not man for business. He recognizes how greatly private monopoly of industry and credit imperil the prosperity and welfare of our people, and that the policy of accepting private monopoly as a permanent condition and having the Government fix prices (particularly on the basis of inflated capitalization) would amount to nothing less than the betrayal of the republic into the hands of the money masters.

La Follette can be relied upon to adopt and to pursue unflinchingly such course of action as is essential to industrial liberty in America. Each day gives new evidence that the American people are learning to understand and to appreciate his qualities, and that an even greater number are looking to him as their leader.

1912 was not the end of La Follette’s presidential ambitions. He ran again twelve years later, this time forming a third party. And his first choice for running mate? His old friend Brandeis, who apparently was not even remotely tempted by the offer. La Follette ended up getting 16.6% of the vote, one of the largest results for a third party candidate in American history. But he only won in one state (Wisconsin, of course) and he was so worn out by the campaign he died seven months later.

Filed under: brandeis | Leave a Comment

Louis D. Brandeis and the NAACP

Louis D. Brandeis has long been viewed by many as a paragon in the field of law: a lawyer who mastered corporate law and also spent much of his career in public service, and who later became a Supreme Court justice who wrote groundbreaking opinions that defended the rights of individuals. But in 2001, Christopher A. Bracey created a small bombshell with an atricle that challenged that view.

The main point of “Louis Brandeis and the Race Question” (52 Alabama Law Review 859) should be non-controversial: that no human being is perfect and that everyone has feet of clay and blind spots. But it was the blind spot Bracey accused Brandeis of having that caught everyone’s attention: the fact that Brandeis appeared to have done nothing during his long career to advance the cause of civil rights.

There were many reactions to Bracey’s article, but there was an incident mentioned in one of the responding articles that I wanted to bring up here. In 2007, Larry M. Roth wrote “The Many Lives of Louis Brandeis: Progressive-Reformer. Supreme Court Justice. Avowed Zionist. And a Racist?” (34 Southern University Law Review 123.) (A a tip of my hat to Lisle Baker for bringing this article to my attention.) Among the various defenses Roth makes for Brandeis, he mentions that Brandeis was working with the NAACP to bring a case before the Interstate Commerce Commission that would challenge segregation on the nation’s railroads.

This was news to me. I have read every biography about Brandeis and I had never heard any mention of a connection between him and the NAACP. Intrigued, and a bit skeptical, I decided to look into the matter. As it turns out, it actually happened. Unfortunately, the historical record of the incident is very skimpy. I am listing below everything I could find out about it. If I come across any more information in the future, I will add it at the bottom of the post.

Roth cites volume 9 of the Oliver Wendell Holmes History of the Supreme Court of the United States (The Judiciary and Responsible Government, 1910-21 by Alexander M. Bickel and Benno C. Schmidt, Jr.). But that book only briefly mentions the matter in a footnote on page 785. It cites as its source the 1967 book NAACP: A History of the National Association of Colored People, Volume 1: 1909-1920 by Charles Flint Kellogg. This book devotes a paragraph on pages 204-205 to the matter, which is worth quoting in full:

The Interstate Commerce Commission was the next target in the move to eliminate discrimination in transportation facilities. Florence Kelley sought the help of Louis Brandeis who was at that time counsel for the Consumer’s League. [first footnote] Brandeis advised the Association that the best approach was to petition the Commission for relief, citing definite cases in support of their contention. Thereupon the NAACP board dispatched Montgomery Gregory of Howard University to collect evidence and take photographs of Jim Crow car conditions in the deep South. Gregory’s investigations covered the lesser as well as major railroad lines, and the waiting room and dining facilities in a number of Southern cities. By the end of 1915, Arthur Springarn and the legal committee had “almost perfected” the cases, which were to have been presented by Brandeis. Brandeis was appointed to the United States Supreme Court in January, 1916, however, and Albert Pillsbury agreed to make the presentation. [second footnote] As with the Oklahoma cases, the entry of the United States into the war prevented the continuation of the Interstate Commerce Commission cases …

Hoping to find ever more information, I looked up all of the sources cited in the above paragraph. The first footnote cited page 143 of Impatient Crusader: Florence Kelley’s Life Story, written, coincidentally, by Brandeis’ sister-in-law, Josephine Goldmark. This turned out to be a red herring, as the information on this page related to Brandeis getting involved in Muller v. Oregon. In fact, there is no mention at all of Kelley’s long involvement with NAACP in the biography — an omission I find rather interesting.

If Impatient Crusader doesn’t explain how Brandeis got involved in the case, volume three of Mel Urofsky and David Levy’s Letters of Louis D. Brandeis and the Brandeis papers at the University of Louisville provide some clues. Folder NMF 69-3 of the papers holds a September 10, 1914 letter from May Childs Nerney, secretary for the NAACP board of directors:

Under date of July 24 you wrote Mr. [Oswald Garrison] Villard that it might be possible for you to see either Mr. Brinsmade or myself after Labor Day in your Boston office in regard to the possibility of the Interstate Commerce Commission considering the condition of Jim Crow cars in the South. The Association is very anxious to press the matter and either Mr. Brinsmade or myself will go to Boston to see you at any time you may appoint.

Unfortunately, there do not appear to be any copies of Villard’s letter or Brandeis’ response to him in the papers. Brandeis’ reply on September 18 to Ms. Nerney is reprinted on pages 297-298 of Letters:

… So far as I know, I shall be in the city on next Wednesday, and could see you at 11:00 o’clock on that day. I have great doubt, however, that it would be worth your while to come to Boston for that purpose alone, as it does not seem possible that I should give you any advice of value in regard to the Jim Crow car situation, and the work I have on hand would prevent my entering upon an investigation of the matter. I shall probably be in New York in the near future, and if you should prefer, will make an appointment there.

Apparently, Miss Nerney did go up to Boston, because on September 28, the NAACP board attorney, Chapin Brinsmade, wrote to Brandeis:

Will you confirm my understanding of what you told Miss Nerney? Miss Nerney understood you to say that our proper procedure will be to file with the Commission, a formal petition for a general investigation of conditions on interstate trains throughout the country, in order to determine to what extent there is discrimination against colored people in respect to the quality of service furnished, citing in our petition as many specific instances of discrimination as possible. Can we petition for an investigation of any interstate railroad or boatline as to which we cannot cite actual cases of discrimination? I should greatly appreciate any suggestions you may make in this connection.

Brandeis’ September 29 reply to Brinsmade can be found on page 305 of Letters:

I should greatly doubt whether the Interstate Commerce Commission would, upon the filing of a formal petition, enter upon a general investigation of conditions of service to colored people on interstate trains.

My advice to Miss Nerney was that petitions be filed with the Commission, seeking redress for failure to provide reasonable accommodations on such railroads as appeared to be particularly serious offenders, and be prepared to make full proof in those cases.

After the presentation of a number of such petitions, the Commission might be induced to undertake a general investigation, but I should greatly doubt whether it would do so in the first instance. I am inclined to think that before instituting any proceeding, it would be advisable for you to talk this matter over with Mr. James W. Carmalt, one of the attorneys of the Commission, who is associated with Chairman Harlan’s office. He could probably give you much better advice than I. If you will show him this letter, it will make clear to him the point I have particularly in mind.

That is the extent, that I can find anyway, in Brandeis’ surviving correspondence of any letters dealing with the NAACP. (Chairman Harlan, by the way, is James Harlan, the son of John Marshall Harlan, and boyhood acquaintance of Brandeis.)

The other footnote in the NAACP paragraph cites various minutes of the NAACP board of directors and three articles from The Crisis, a magazine put out by the NAACP.

The August 4, 1914 minutes (a month before Nerney’s letter to Brandeis) states:

Steps have been taken to procure a conference with Mr. Brandeis in order that he may induce the Interstate Commerce Commission to undertake an investigation of the Jim Crow situation.

The October 6, 1914 minutes (a week after Brandeis’ letter to Brinsmade) states:

The most important piece of work undertaken during the month has been the attempt to put the Interstate Commerce Commission on record as to their attitude on the Jim Crow situation in the South. Mr. Brandeis has advised the Association to petition the Commission for relief, citing definite cases. The Attorney of the Association is now collecting data for that purpose.

The September 13, 1915 minutes state:

A summary of the report of Mr. Gregory who recently took a four weeks’ trip to investigate Jim Crow cars in the South will appear in the next issue of The Crisis to be followed by a series of articles on the same subject. His trip cost the Association about $200. Prof. Gregory’s itinerary included Columbia and Sumter, S.C.; Augusta, Tennille, Savannah, Waycross, Columbus, La Grange and Atlanta, Ga., Birmingham, Opelika, Tuskegee, Montgomery, Selma and Uniontown, Ala.; Meridian, Miss.; New Orleans, La.; and Chattanooga, Tenn.; and his investigations covered the following railroads: The Southern, Seaboard, Atlantic Coast Line, Augusta Southern, Central of Georgia, Louisville and Nashville, Queen and Crescent, West Point, Alabama and Great Southern, and a number of smaller lines. This material is to be presented to Mr. Brandeis of the Interstate Commerce Commission to be used by him in connection with the Jim Crow car case which is now in the hands of the Legal Committee.

The minutes of February 13, 1917 simply state that Albert E. Pillsbury will be requested to represent the Association before the Commission. The other three citations in the footnote are to the three issues of The Crisis (December, 1915, and January and February, 1916) which ran articles based on Gregory’s findings while riding the trains in the South.

And that is all I can find in the historical record. It is not much of an incident: Brandeis almost took part in some cases that never made it to the ICC. However, while it doesn’t answer the question of why Brandeis didn’t involve himself more in civil rights issues, it does show that he was not against the cause. It is interesting to speculate what might have happened if Brandeis’ nomination to the Supreme Court had not been approved by the Senate. (It was a close call. Roth points out that one of the stumbling blocks was a rumor circulating among the southern Democrat senators that Brandeis wanted to desegregate the railroads. Maybe they had heard that he was working with the NAACP.) Perhaps his brief association with the NAACP would have lead to a deeper relationship with them. His protégé Felix Frankfurter was a member of the NAACP’s National Legal Committee. Is it so far fetched to imagine that Brandeis would have followed suit?

Filed under: brandeis, Harlan | Leave a Comment

While going through old newspapers, I found a column from 1924 describing the home lives of various wives of justices sitting on the Supreme Court at the time. It is a gossipy little item, precisely the type journalism Brandeis railed against in his “Right to Privacy” article. The column seems to have been part of an anonymously written series commenting on the social life in Washington. There are no great revelations given, but I am reprinting the part about the Brandeis home life here just so people can have an idea of what it would have been like to visit the Brandeises during the 20’s. The excerpt starts just after a paragraph devoted to Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.’s wife.

“Boudoir Mirrors of Washington”

Anonymous Word Pictures of Society Leaders of the National Capital.

Supreme Court Wives

…Then there is Mrs. Louis Brandeis — easily one of the most outstanding ladies of the Supreme Court group. She is handsome, with great dark eyes, good complexion, and snow white hair. And she carries herself well. Why shouldn’t she? Isn’t she one of the Goldmarks, the family that has given Pauline and Josephine Goldmark to the world, besides Mrs. Brandies[?] Hers is a justifiable pride. She was active in suffrage work. She has two daughters, both good feminists.

Running true to tradition, Susan Brandeis worked for suffrage after she graduated and she is now practicing law in New York. You know Elizabeth is executive secretary of the Minimum Wage Commission of the District of Columbia. When the minimum wage law in the district was declared unconstitutional, by a local court, it went to the Supreme Court. There was keen speculation as to what Judge Brandeis would do and how he would vote. But he declined to sit. He had previously argued a similar case and his sympathies were well known. He calls it a matter of ethics. But I think the labor people say it was mere etiquette.

The Brandeis home is not the storm center of the socially elect. If you want your Washington all jazzed up you don’t go there. It is the socially minded people — men and women who care how the other half live, and why they don’t live longer and more happily — these are the people you meet. They are interesting men and women; when they speak you may not agree with them but their remarks are well worth listening to.

Lion hunting isn’t a Brandeis pastime, but the really big game generally gets around to their preserve sooner or later. Of course, you find people who try to sneak up in the night and hang a red flag over the door. Cochineal isn’t brewed in the cellar. The reddest thing in the Brandeis household is the warm glow of human sympathy and understanding.

Ladies of fluffy ruffles, lounge lizards and all the vapid, brainless excitement chasers, go round the block. But if you realize life, in its best, broades[t] sense, just go in.

Filed under: brandeis, Elizabeth Brandeis Raushenbush, Susan Brandeis Gilbert | Leave a Comment

Frank Brandeis Gilbert died on May 14, 2022, at the age of 91. He was the last surviving child of Susan Brandeis and Jack Gilbert. His cousin Walter Raushenbush is now the last surviving grandchild of Louis Brandeis.

As a child, Gilbert would spend his summers vacationing with his parents and grandparents in Chatham, Massachusetts. In a previous post, I wrote about how he started a newspaper for their grandfather to read. Gilbert recalled that newspaper in a recent interview, stating, “It’s poignant that his last letter to me was about the Gilbert News Service shutting down.”

Gilbert got a bachelor’s degree in government from Harvard in 1952, as well as a law degree from Harvard Law School (his grandfather’s alma mater) five years later. Gilbert showed his love for Harvard by being the chairman of the graduate board of the Harvard Crimson for 20 years.

Gilbert started his legal career performing work in public housing and city planning, but he made his name in historic preservation. He was instrumental in keeping Grand Central Terminal from being demolished during the 1960s. After that, he helped create historic districts in over 100 cities.

Like his sister, Alice Popkin, Frank was a big supporter of the law school at the University of Louisville, where he attended many Brandeis Medal events. He was also a constant source of information for me in all of my research on his grandfather. He will be greatly missed by me and many others.

Donations in his memory can be made to the Frank and Ann Gilbert Scholarship Fund at Brandeis University (be sure to mention the name of the scholarship in the form) or the Round House Theatre in Bethesda, Maryland.

Filed under: brandeis | Leave a Comment

Tags: brandeis

This post has a special guest author: Louis Brandeis’ great-grandson, Paul Raushenbush. Paul is the Senior Advisor for Public Affairs and Innovation at the Interfaith Youth Core, and is the grandson of Brandeis’ daughter Elizabeth. He sent me the following tribute to his grandmother on what would have been her 126th birthday. I enjoyed it so much that I asked his permission to reprint it here, which he graciously granted.

Today, April 25, in 1896, Elizabeth Brandeis was born to her parents Alice Goldmark Brandeis and Louis D. Brandeis and older sister Susan.

I have been writing the story of Elizabeth Brandeis – or E.B. to those who knew her – for the past several years, finding old photo albums, caches of letters and memorabilia, searching her archives at Wisconsin Historical Society and Schlesinger Library, and stumbling across information that has made my grandmother’s life become vivid and meaningful and relevant for my life and our moment. Before I finish that work, I want to offer a sketch of her life, hopefully so people will join me in celebrating her birthday today.

E.B. was a shy girl, who grew up missing classes at the rather uptight Miss Winsor’s academy; playing alone after school, teaching herself to roller skate along the Charles river in Boston. However, she had powerful women role models surrounding her including her aunts Josephine and Pauline Goldmark as well as a cadre of other strong women who were around them such as Florence Kelly, Jane Adams, Julia Lathrop, Francis Perkins, Lillian Wald, and Elizabeth Glendower Evans. They were women who were – excuse my French – kick ass – who were dedicated to improving working conditions and increasing wages, eliminating child labor, and overall seeking justice and dignity for humanity.

Once at Radcliffe, Elizabeth found the friends she had been seeking and became more herself; graduating Phi Beta Kappa in Economics, and voted head of the student body while playing basketball, acting in plays such as the Emperor Has No Clothes, and leading the college socialists.

After college she moved to D.C. where she and one other woman named Clara Mortenson Beyer administered the nation’s first minimum wage law. The law was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court, a decision in which her father recused himself. E.B. decided to explore the intersection of law and economics, and as none of the East Coast schools would accept women, including her father’s beloved alma mater, she decided to attend classes at the Law School for the summer at University of Wisconsin in Madison in 1923.

In her Torts class, she saw a handsome young man who was taking the law class, although he was a lecturer in Economics under John R. Commons. His name was Paul Rauschenbusch and he was the son of Pauline and Walter Rauschenbusch. Elizabeth found the economics department more interesting than law and that fall joined as first an MA and then. Ph.D. In 1925, Elizabeth Brandeis and Paul Raushenbush made the national papers as they eloped to spend the next three weeks canoeing in Canada and three years later they had a son, Walter, my father, the same year that E.B. earned her Ph.D. in Economics.

E.B. and Paul both taught in the economics department – scandalous for the time – and there they came up, along with their friends Harold Groves and Governor Phil LaFollette with a plan for Unemployment Compensation that eventually would be the first UC bill in the nation and would be the blueprint for FDR’s Social Security Act of 1935. Paul would go on to administer the Wisconsin Unemployment Compensation Bill for the rest of his career.

One of her students was Robert Lampman who became known as the intellectual architect of the War on Poverty who recalled later how E.B.’s classroom had prepared him for his work in Washington: “I was doing what Elizabeth Brandeis knew how to do, and took her back to the Brandeis brief of her father, when he was a young lawyer–of gathering the kinds of basic information you need to make an enlightened decision about child labor or disability or whatever.”

In 1959, E.B. was appointed chair of the Governor’s Committee on Migratory Labor and was instrumental in bringing labor justice to migrant workers in Wisconsin. Jesus Salas, who was known as the Cesar Chavez of Wisconsin migrant workers wrote to me in an email: “Your grandmother was my mentor. She was extremely interested in expanding services to migrant families, to women and children in the migrant labor camps. She was scandalized by the conditions of the migrant labor camps. At receptions at her home, I recall how gracious she was being the host, again, the gatherings were on behalf of migrant issues, but none of us wished to be anywhere else than with your grandmother.”

At her retirement event – which was, naturally, a knowledge gathering symposium on effective state labor legislation – one of the speakers was Clara Penniman who was the first woman faculty member of the Political Science Department at Wisconsin; later becoming the first woman Chair of the Department, and was the founder and first director of the Center for the Study of Public Policy at Wisconsin that later became the Lafollette School for Public Affairs. She started her speech by saying: “I met E.B., as you might expect, in an organization that attempts to bring knowledge to bear on public problems.” In her conclusion she offered this assessment: “It seems to me that the appropriate single word to describe E.B. is concern. Concern for the welfare of students, concern for the personal problems of friends and associates, concern for a wide range of public problems. This is concern that is translated not into negative criticism or bemoaning of life and the world but is translated into positive problem-solving action.”

E.B. always considered what she did “Action Research,” meaning the purpose of her research was to make her ideas and the solutions better to serve the needs of the people. Recently I was searching Elizabeth Brandeis online and saw that the Department of Labor had decided to name a research initiative after her. The Elizabeth Brandeis Unemployment Insurance Research Center will be founded at a University to promote ‘Action Research’ to ensure that Unemployment Insurance reaches those who need it most.

What a supremely appropriate effort to be attached to E.B.’s name.

So, Happy Birthday E.B.! I look forward to sharing more when the book is complete but glad today that you can know her just a bit more and celebrate with me.

Filed under: brandeis, Elizabeth Brandeis Raushenbush, Paul Raushenbush | Leave a Comment

The Death of Samuel D. Warren

The names Louis D. Brandeis and Samuel D. Warren are inextricably linked due to their co-authorship of the landmark article “The Right to Privacy,” but for much of Brandeis’ life the men were linked in many other ways. While Brandeis was academically first in their class at Harvard Law School, Warren was right behind him. Rather than fostering a rivalry, the two men became close friends and they ended up forming the firm Warren and Brandeis in Boston a year or so after they graduated. Warren’s family was one of the most prominent families in Boston and not only did they steer a lot of important business to the fledgling firm, but they also welcomed Brandeis with open arms.

Warren’s father passed away in 1888, an event that would end the professional partnership between Warren and Brandeis and would lead to ramifications that would haunt Brandeis for decades.

The source of the Warren family’s wealth was a paper mill in Maine and because of the elder Warren’s death, it looked like the mill would have had to be sold. In order to prevent that from happening, Brandeis and Warren devised a complicated trust that created a board that ran the company in such a way that its profits could be shared equally amongst all of the Warren family members. One immediate effect of this arrangement was that Warren had to give up the practice of law, which he loved, so that he could run the board.

The other effect took a longer turn to develop and was much more insidious. For the first few years, the mill continued to turn a healthy profit, but after a while, the combination of a recession and increased competition resulted in smaller payouts to the family. The decrease in profits infuriated Warren’s brother Edward (or Ned, as he was known within the family) who became convinced that not only was Warren mismanaging the mill but that the trust had been created in such a way to benefit Warren at the expense of the rest of the family. After years of negotiations and threats, Ned filed suit against Samuel in 1909. The suit never made it to court however, because in February 1910, Samuel ended up committing suicide.

The subject of Warren’s suicide and its impact on Brandeis’ nomination to the Supreme Court are the subject of an article written by yours truly that is published in the latest issue of the Journal of Supreme Court History (volume 46, issue 3). The article came about as the result of the discovery of two letters in the Brandeis papers collection at the Louis D. Brandeis School of Law at the University of Louisville. While the collection has around 250,000 items that were donated to the law school by Brandeis, various other items have trickled into the collection over the years. Some of the new material came from Nutter McClennen & Fish, which is what the firm founded by Warren and Brandeis is called now. While going through collection a couple years ago, two letters that were given to us by Nutter caught my eye.

While researching for his book Brandeis: A Free Man’s Life, Alpheus Mason came into possession of a letter written by Richard Walden Hale, a Boston lawyer who worked occasionally with Brandeis, most notably on the creation of Saving Bank Life Insurance. (Interestingly, Hale was also the founder of a law firm that is still extant: WilmerHale.) Written shortly after Brandeis’ death and in apparent response to a friend’s inquiry into their relationship, Hale makes caustic comments about Brandeis’ behavior in a number of matters, including the Warren family trust and subsequent lawsuit. Mason showed this letter to Edward McClennen, who was one of the partners at Brandeis’ firm and was also the man who spearheaded Brandeis’ defense during the Senate hearings over Brandeis’ nomination to the Supreme Court. McClennen wrote a letter back to Mason that refuted all of Hale’s points, while also including a number of anecdotes about his former boss and mentor.

I’m not sure what happened to Mason’s copies of the letters, but McClennen apparently kept his copies at work, which is how they got included in the batch of Brandeis related files that Nutter donated to the law school. Despite having been gathered for his biography, Mason made scant use of the letters, and none of Brandeis’ later biographers appear to have seen them, so much of the information in them is new. They touch on many points of Brandeis’ career, but the most significant aspect about the letters is the light they shed the impact Warren’s death had on Brandeis’ nomination. I had long wondered why so many of Brandeis’ peers in Boston were so opposed to the nomination. I won’t reveal the answer here — you’ll have to read the article to find out for yourself. Suffice to say, there was more to it than reactionary attitudes and anti-Semitism.

Filed under: brandeis, Journal of Supreme Court History | 1 Comment

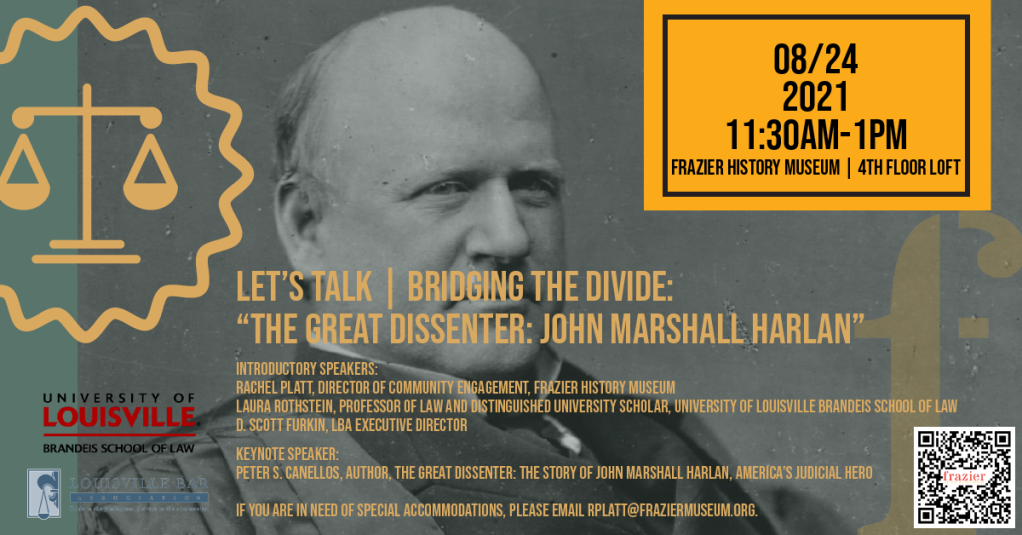

When I was first put in charge of the Brandeis and Harlan papers here at the Louis D. Brandeis School of Law at the University of Louisville, most of the attention our collection generated was directed towards Brandeis’ papers. People were aware of Harlan and there would be the occasional reference question about him, but he seemed to be a marginal character in Supreme Court history. However, his stature has grown steadily during the last 25 years — so much so that two biographies about him have come out in the past two years.

Steve Luxenburg’s Separate was actually a group biography of four people which functioned also as a history of segregation in America. Similarly, The Great Dissenter: the Story of John Marshall Harlan, America’s Judicial Hero by Peter S. Canellos, the managing editor of Politico, tells the story of the plight of African-Americans throughout the 19th century through the lens of a dual biography.

The book is primarily a straightforward biography of Harlan, and as such, it covers the usual beats: his upbringing in Kentucky, his Civil War experiences, his political career, and an in depth look at his Supreme Court opinions, particularly the ones on civil rights. But, in an inspired stroke, Canellos gives the story an added depth by contrasting Harlan’s life with another biography: that of Robert Harlan.

Robert Harlan was a former slave who had been raised in the Harlan household. All through John and Robert’s lives it was rumored that the two were half-brothers. This has recently been disproved through DNA testing, but what is undeniable is that the two men had a brotherly bond. And Robert led a life that was just as exciting as John’s. He made a fortune during the California gold rush, raced horses throughout America and England and became one of Cincinnati’s more prominent citizens.

Robert’s success would not last forever however. As Jim Crow laws proliferated in the late 19th century, they blighted the lives of Robert Harlan and African Americans throughout the country. By incorporating the story of Robert Harlan into John Marshall Harlan’s story, Canellos gives the narrative a poignancy that other Harlan biographies lack. He is also thus able to answer a question that has bedeviled other historians: how did a former slaveholder who opposed emancipation and the Reconstruction amendments come to be one of the most outspoken advocates for civil rights on the Supreme Court? The answer is that because of his relationship with Robert Harlan, he could see the benefits of the amendments and the Civil Rights Act at first hand, as well as the damage that was caused by their dilution by the courts.

There are other pleasures to be found in the book. Canellos refutes the charges of racism levied at Harlan, and discusses Harlan’s dissents in cases on subjects other than civil rights that have proved to be just as prescient. Overall, The Great Dissenter is the best biography of Harlan written so far and should be read by anyone interested about this great American and/or the history of civil rights.

If you live in the Louisville area and would like to hear Canellos talk about the book and maybe even have him autograph a copy of it, the Louis D. Brandeis School of Law is co-sponsoring a lecture by Canellos with the Frazier History Museum and the Louisville Bar Association on August 24. Click on the link for details.

Filed under: Harlan | Leave a Comment

I am pleased to present another guest post from Laura Rothstein, former Dean of the Louis D. Brandeis School of Law at the University of Louisville and Brandeis groupie extraordinaire.

Louis Brandeis wrote many, many letters and notes during his lifetime. Many were to his mother and brother in Louisville. Many of these family letters were given to the University of Louisville Brandeis School of Law and are archived in the Handmaker Room of the Law Library. Occasionally a new discovery is added.

David Wolfson’s mother, Isabel Grossman, was a student at Adath Israel Temple (now just called The Temple) in 1937. She sent birthday greetings on behalf of her class to Louis Brandeis. Being a good correspondent, he wrote back. The note from Louis Brandeis was found by David Wolfson, an attorney in California, when his cousin Phil Grossman asked him about a letter David’s mother had received from Lou Gehrig. In the folder where that letter was found, the letter from Justice Brandeis was also discovered. When Phil Grossman (a 1980 graduate of the law school) contacted the law school about this, the letter from Isabel was discovered in the Law School archives. Reproductions of both letters will soon be displayed at The Temple library.

The contents of the letter from Isabel Grossman are the following:

November 7, 1937 {Brandeis’s birthday is November 13}

2140 Bonnycastle

Louisville, Kentucky (handwritten note by Brandeis – 6/29/38)

Dear Justice Brandeis:–

Class G of the Adath Israel Temple wishes to congratulate you on your birthday. We are very proud that you too, are a native of Louisville.

I am the great granddaughter of Myer and Jane Goldberg, who were great friends of Mr. Louis {Lewis} Dembitz. One summer night in Civil War times, Mr. Dembitz came to my great-grandparents home. They discussed the War so heatedly that Mr. Dembitz in his excitement jumped up and sat on the drum stove. My great grandfather who liked a practical joke, went out of the room unnoticed by the others and brought in some wood to start a fire in the stove. So engrossed was Mr. Dembitz in his conversation that he did not become aware of his seat until the stove got warm. I am telling this story because I knew you would be interested in the man for who you were named.

With best wishes for your birthday

I remain

Yours sincerely

Isabel Grossman

c/o Class “G”

Adath Israel Sunday

School, 834 S. 3rd St.

The reply from Louis Brandeis, which was donated (including the envelope with the return address of the Supreme Court and a three cent stamp – which did not change until 1958 to 4 cents –) is the following:

Chatham Mass

June 28, 1938

Dear Isabel Grossman

The work of the court compelled deferring until the long vacation the pleasure of thanking class G of Adath Israel Temple for the kind birthday greeting.

The story which you tell of my Uncle Lewis Dembitz interests me much.

With Best wishes

Cordially

Louis D Brandeis

The contents of both notes highlight some interesting facts.

First, Lewis Dembitz was a well-known and highly regarded attorney in Louisville. There are many interesting stories about his forceful personality and he is credited as being part of starting the Louisville Bar Association. He was the brother of Louis Brandeis’s mother, Fredericka Dembitz, and he was politically active, including attending the 1860 Republican National Convention that nominated Abraham Lincoln. Although the letter from Isabel states that Louis Brandeis was named for his uncle, there is no evidence that that was the case. It is more likely that he was named for the city in which he was born. The pronunciation of his name was also the French “lou-ee”. It is true, however, that Louis so admired his uncle that at age 13, he changed his middle name from David to Dembitz.

Isabel’s note references the Civil War. The Brandeis family members were abolitionists, and Louisville was at a key crossroads during the Civil War – geographically and politically. Louis Brandeis’ first memories are at age 6 serving food and coffee to Union soldiers on his front yard with his brother and mother.

Lewis Dembitz was a practicing Orthodox Jew. Louis Brandeis and his immediate family did not observe Jewish traditions, but Louis admired his uncle and observed his practices and it is believed that Lewis Dembitz was influential in Louis Brandeis becoming the leader of the American Zionist movement for several years.

Second, the reply from Louis Brandeis notes an apology for the delayed response and explains that the work of the Court had deferred his reply to the birthday wishes. Louis Brandeis believed strongly in the importance of taking time to relax and refresh – every day and throughout the year. One of his most noted quotes is that “I soon learned that I could do twelve months work in eleven months, but not in twelve.“

Brandeis had a home in Chatham, where he spent the summers, with his four grandchildren being much a part of summer relaxation. That home is still owned by one of the grandchildren.

It is noteworthy that 1938 was the year before Louis Brandeis retired from the Court (1939). He died in 1941.

While perhaps not sufficient to be worthy of a Ken Burns documentary, these two notes provide an opportunity to explore the history and life of two noted lawyers from Louisville as well as some history about Jewish life in Louisville. What a “beshert” discovery, and how generous of David Wolfson to share it with the Louisville community and for Phil Grossman to facilitate the opportunity to share these documents and the story behind them.

Filed under: brandeis, Laura Rothstein, Lewis Dembitz | Leave a Comment